Spotlighting Black Trans & Queer Power and Possibility in the Carolinas

At Cypress Fund, our grantmaking, donor organizing, and funding interventions are grounded in a Black queer feminist framework—a political and cultural tradition that directs our work toward the people most impacted by systems of oppression and most equipped to dismantle them. When we fund organizing that centers those most vulnerable as trusted sites of liberatory experimentation and collective care, we shift the conditions for everyone. That’s why we invest in Black trans women and femmes who live at the crossroads of violence, resistance, and joy. As mainstream systems fail, Black trans women and femmes have built mutual aid networks, physical and mobile hubs, and community-led responses to care and safety.

In this month’s blog, we’re spotlighting the Harriet Hancock LGBT Center and the Pauli Murray Center for History and Social Justice, two loving institutions in the Carolinas that are doing this work every day. Both serve as anchors for queer and trans communities, offering cultural memory, resources, and refuge. They need our love and support.

The South as a Birthing Ground: Queer and Trans Survival in the Carolinas

Black queer folks, and trans folks more specifically, have always been square in the middle of white supremacy’s violent obsessions. Proponents of the myth of white supremacy are frighteningly obsessed with ensuring oppressive sexuality and gender performances create a universe of indifference, selective silence, and coordinated attacks on Black folks and young people with deviant gender and sexuality. Saidiya Hartman writes powerfully about these campaigns in Scenes of Subjection and Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments. The Carolinas are a birthing site of that centuries-old obsession.

Over the past decade, the North Carolina state legislature has passed many laws, but for many, only one stands out: House Bill 2 (HB2). Passed in March 2016, HB2 made it illegal for transgender people to use public restrooms that align with their gender identity in schools, government buildings, and state agencies. The bill was a direct backlash to a Charlotte City Council ordinance that had expanded anti-discrimination protections to include gay and trans people. The response from the community was immediate and bold. Residents organized noise protests, mass marches, small business coalitions, and occupied the halls of the state legislature. At the center of this mobilization were Black femme leaders like Ashley Williams of Charlotte Uprising.

Hysteria around trans folks and any aspect of their lives, like HB2, creates a narrative of delicate (read: lily white and pure) women and children, public spaces, and psyches that are corrupted from their previously safe, secure, and state-controlled status. The hysteria, which anticipates and proceeds violence, hinges on a boogeyman whose threat looms as an omnipresent phantom. The same year HB2 was voted into state law, the police killing of Keith Lamont Scott in Charlotte ignited another wave of protest—one that further illuminated the deep connections between the fight for Black and queer life. For months, Charlotte residents organized in response to this flashpoint, bringing together people across movements who understood that racial justice, gender justice, and queer liberation are inseparable.

Some years are marked by a hysterical frenzy of oversized legislation — like the countless federal bills around healthcare and educating attack reproductive care for women, trans folks, and young people — and others are marked by subtle cultural cues and symbolic points of improvement. Black activists and writers have long written about and organized against the long arc of fascism for Black folks. Many people who have been previously protected by the status quo of authoritarian rule have begun calling the thing what it is: by design, deeply oppressive and larger-than-life in its violence. These revelations ring too little too late for Black queer folks who have been organizing to fill the gaps in care, safety, and security in this violent nation’s history.

Legislatures, police forces, schools, religious institutions, nonprofits, and other community formations have been murderous and cruel to queer people, especially Black and Native trans women and young folks. We remember the life and love of Nex Benedict, a non-binary 16-year-old of Choctaw ancestry who was assaulted by multiple classmates in a girls' bathroom at their school in Oklahoma in 2024. Though Nex initially survived the assault, the injuries they sustained were fatal. Nex loved their cat, Zeus. We also mourn and celebrate the life and love of Pebbles LaDime “Dime” Doe, a 24-year-old Black trans woman murdered in South Carolina in 2019. Dime’s loved ones remember the warmth of her hugs and the joy she carried. The federal indictment in the state’s case against Dime’s murderer marked the first application of the Matthew Shepard and James Byrd Jr. Hate Crimes Prevention Act to a case involving a transgender person. But this so-called milestone rings hollow in a legal system that lacks the care and rigor required to protect Black life, let alone Black trans life.

Community Spotlight: The Harriet Hancock Center

Since 1993, the Harriet Hancock Center has served the LGBTQ+ community across South Carolina, with a central focus in the Midlands. It was the first LGBTQ+ center in the state and remains the only one to serve all ages. The Center was named for attorney Harriet Hancock, a cisgender, straight white woman, who, among many others, championed the movement for LGBTQ+ rights in SC in the late 80’s and early 90’s, leading to the founding of South Carolina Gay & Lesbian Pride Movement (SC GLPM), the precursor organization to the Harriet Hancock Center and SC Pride. Hancock made LGBTQ+ rights her priority after her teenage son came out to her as gay.

Today, the Center’s programming is grounded in peer support groups, social activities, educational events, and partnerships with grassroots organizations. One of their projects and priorities is a resource guide that is maintained on their website and includes a vetted network of medical, behavioral, and mental health providers, as well as inclusive barbers, dietitians, and physical therapists. Their peer groups, like Queer x BIPOC and Queer x Disabled, create intentional space for folks who live full lives at intersections.

Executive Director Cristina Picozzi (they/she) shared with me their pride in the safety and relationships built through the Center’s work and how the team compensates and uplifts community facilitators. Collaborations with groups like Queer Writers of Columbia, the Palmetto State Abortion Fund, and CAN Community Health for AIDS / HIV reflect a deeply intersectional approach. Cristina is most proud of the safety, friendships, and community that the Center has been able to curate for folks through consistent programming and compensated training for community members who facilitate programs.

Here’s how you can support The Harriet Hancock Center:

- Save the Date! The Center’s 2nd annual Legacy Gala will happen on Thursday, September 11 from 7:30 to 10:30 p.m. at the Columbia Museum of Art. This year’s theme is “Are You a Friend of Dorothy? No Longer a Secret, Never Again Silent” is a nod to the speakeasies and safe spaces our community built throughout history. These places of joy, safety, and resistance existed long before widespread acceptance or legal recognition.

- Donate, sponsor, or purchase gala tickets: https://harriethancockcenter.networkforgood.com/projects/200241-harriet-s-heroes-giving

- Volunteer or offer services to support the center in their $100,000 fundraising goal for the gala

- Visit harriethancockcenter.org/volunteer to get involved

- Follow them on Instagram @harriethancockcenter or on Facebook and amplify their content!

Community Spotlight: The Pauli Murray Center

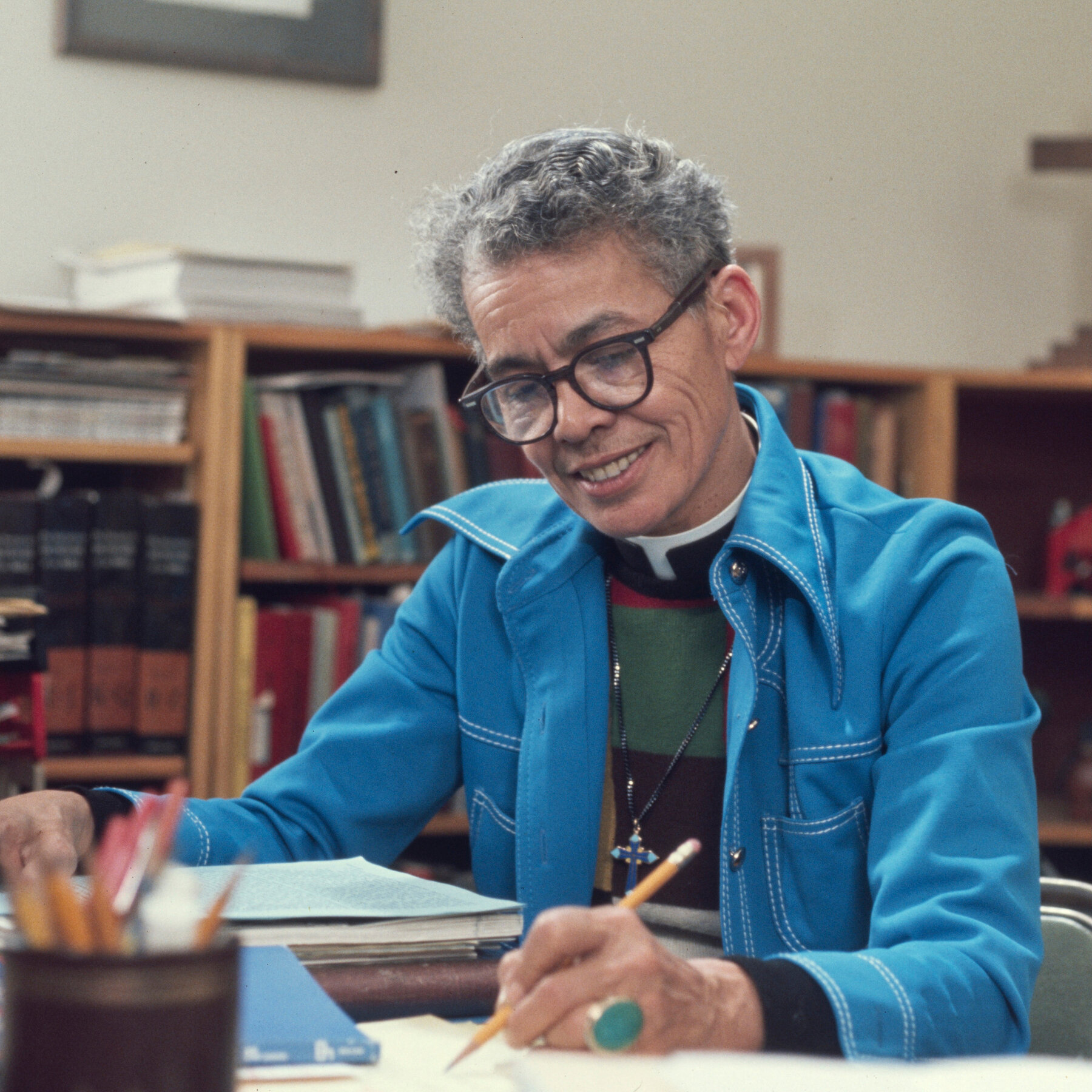

Located in Durham’s historically Black and working-class West End neighborhood, The Pauli Murray Center for History and Social Justice is a nationally registered historic site and national treasure that is both a house museum and a social justice hub. The Pauli Murray Center honors Pauli’s life and legacy by working closely with their descendants and local movement groups that drive contemporary social change.The center sits beside the preserved home of Rev. Dr. Pauli Murray (she/he/they), a Black genderqueer legal scholar, poet, groundbreaking Episcopal priest, and organizer who coined the term “Jane Crow” to describe the racialized and gendered systems of oppression faced by Black women and girls. Much of their other legal work built the foundation of civil rights legal organizing for lawyers like Thurgood Marshall, several civil rights and feminist organizations that she built and worked to expand into greater intersectional work, and seminal theological research and writing. You can learn about and access Pauli’s writings, like Song in a Weary Throat: Memoir of an American Pilgrimage and Dark Testament, and move through the center’s resources page.

Built in 1898 by Murray’s grandparents, Cornelia Smith and Robert Fitzgerald, the home has long withstood encroachment from white development. The home is bordered by a former farmland that the city turned into a whites-only cemetery, abutted by confederate monuments, and standing among ongoing gentrification that has destroyed greenspace and exposed the neighborhood to flooding and runoff. In 2010, neighbors rallied to save the house from demolition and raised the funds to preserve it.

Today, the team at the center organizes tours during the week and on some Saturdays, connects queer folks to name and gender change services, hosts drag story hours, and has a social justice teaching fellowship. Christen Ruiz, the Development Director at the center, emphasized to me that the center is not a sterile museum squirreled away in the arts or business district of a city, but a warm space surrounded by neighbors who remember the Fitzgeralds. Christen’s most cherished memory of Pauli is his powerful mantra: “Don’t get mad, get smart.” The words remind her that she is showing up not only in Pauli’s name, but in service to the visionary commitments Pauli held most dear and held onto during trying times.

When I spoke to her, Christen’s invitation was capacious and tender: “come people of faith, trans, queer, Black folks — not to feel like you’re in a tight space of despair and panic. Find comfort in Pauli’s worth and legacy so that you deeply know what you are giving your resources and time to.”

With its sight turned on the center, the current administration is actualizing its mission to further abandon and pathologize Black, trans, and grassroots legacy-in-action, especially in the South. In March of this year, the president wrote an executive order calling for drastic cuts to the federal Institute for Museum and Library Services. In line with the sudden defunding, the Institute sent the center’s staff a termination letter explaining that they would be withholding a $330,800 grant that would be 16% of the 2025 budget and 20% of the 2026 budget. A short explanation was offered: the center “no longer serves the interests of the United States.” Just a few weeks before the funding termination, someone ordered National Park Service’s staff to scrub Pauli Murray’s biography page from the NPS website.

Here’s how you can support The Pauli Murray Center:

- Donate to their annual campaign

- Sign up for a tour or attend upcoming programs

- Follow their educational work and amplify their content on Instagram and Facebook

At Cypress, we believe that funding Black trans and queer organizing is not optional, and it is certainly not a niche. It is central to any strategy rooted in liberation and repair. These two centers represent what it looks like to build institutions of care, resistance, and memory. Let’s show up and love on them.